Highlights

- The BRICS group’s 15th summit did not mark a shift in the global economic order.

- The expansion of BRICS membership weakens, rather than strengthens, the group’s relevance.

- BRICS won’t issue a currency that can rival the US dollar. In fact, it can’t.

BRICS is a great acronym, but a poor concept for a global economic alliance. The BRICS countries — Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa — are a heterogenous bunch, with few common economic policy goals. The group itself was dreamed up by a Goldman Sachs analyst in 2001, in the context of an investment strategy for fast-growing emerging countries. With such a clunky genesis, no wonder its countries struggle to cooperate. Plus, two of the five original members, India and China, are geopolitical rivals, while Russia is a toxic ally.

BRICS is not new. The group began coalescing around the Goldman Sachs acronym almost 15 years ago, holding its first official summit in 2009. Since then, it hasn’t managed to take any meaningful joint action. Its plans for a fibre-optic communications system — the “BRICS Cable” — are in limbo. The New Development Bank, which is a World Bank alternative, has only completed a handful of loan deals, and cut ties with Russia amidst the invasion of Ukraine. The Reserve Contingency Agreement, which is an IMF alternative, never got off the ground.

But perhaps, after a decade and a half of irrelevance, BRICS is about to kick into gear with its 15th Summit, which saw the addition of six new members: Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). We would in fact argue the opposite: this expansion weakens the group. It makes it less likely that BRICS collaboration leads to policy outcomes. First, two of BRICS’ original members, Brazil and India, have strong democratic values and were already feeling uneasy collaborating with China and Russia, even if they saw economic gains in doing so. The addition of Iran, Saudi Arabia and the UAE will further strain the ideological spectrum. In fact, Brazil and India were reportedly opposed to the Chinese-initiated BRICS expansion. The G7 works as an economic forum because its members share ideals of democracy and liberalism. It’s not obvious which common values are shared by BRICS members, other than a vague aversion to US hegemony.

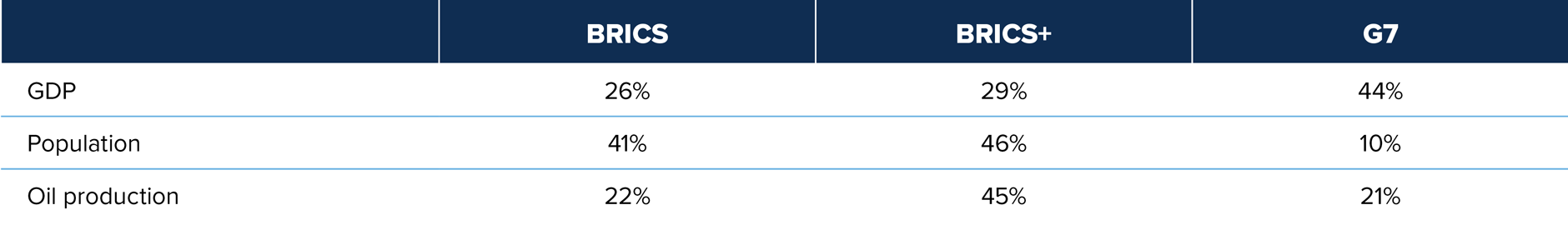

The expanded BRICS encompasses almost half of the world’s population

Groups’ share of world GDP, population, and crude oil production

Source: IMF, World Bank, International Energy Agency. GDP and oil production show annual values for 2022. Population is as of end-2022.

Second, the ineffectiveness of BRICS is not due to its lack of economic and geopolitical power. Original BRICS countries make up roughly 41% of the world’s population and 26% of its GDP. Its ineffectiveness is due to the heterogeneity of its economic and political aspirations. Consensus building won’t be helped by adding three authoritarian “petro-states” (Iran, Saudi Arabia, UAE), two unstable nations (Ethiopia, Egypt), and an economic “basket case” (Argentina) to the mix.

Third, the expansion risks further shifting the balance of power in BRICS towards China, which could cause India, South Africa and Brazil to lose confidence in the forum. China was the driving force behind the expansion, and the six additions are all countries with which China has strengthened its relationship over recent years. China is, by itself, a political and economic force. With or without BRICS, it can impact the global economy. But the potential of BRICS emerging as more than a China proxy, with legitimacy on the world stage, is weakened by recent developments.

The issuance of a BRICS currency — one of the bloc’s proposals — has been touted as a potential disruptor of the US dollar as hegemonic currency. In our view, even if “BRICS bucks” become a reality, it won’t become a major global currency to challenge the US dollar.

BRICS countries are too different to adopt a single currency. Movements in currencies allow a country to absorb economic shocks. Even the more similar eurozone countries have trouble absorbing economic shocks because of their common currency.

A currency is not just a unit of account; it represents claims on assets somewhere. Currently, BRICS countries’ economic model — save for India — is to export a lot and accumulate dollars (i.e., US assets). They need a secondary country to park all their excess savings from selling goods abroad. Currently, the US and other developed countries play that role. If they were to truly decouple from the US and design a closed BRICS trade system, some of the BRICS countries would have to find a substitute for the US and run trade deficits (i.e., import more than they export). But none of the BRICS countries is willing or able to flip their economic model from export- to consumption-driven. Our May commentary explains why China is nowhere near ready to play the role of global consumer.

India could eventually absorb a portion of the trade surplus, but it is too unstable and risky to become the “safe haven” of BRICS. Russia tried to sell oil for Indian rupees — rather than dollars — last year, but the arrangement quickly fell through. India didn’t want Russia buying up Indian assets and Russia didn’t want Indian assets.

BRICS+ countries need somewhere to park 1.4% of world GDP of excess capital annually

Current account balances in US dollars

Source: IMF, annual values, last data point in 2022.

We see the US dollar depreciating over the coming decade. High interest rates, government-driven US growth exceptionalism and geopolitical shocks have left the US dollar significantly overvalued relative to fundamentals. It’s even possible that the US dollar’s safe-haven status loses some shine from US-bred uncertainty. Partisan divisions, the weaponization of the dollar for sanctions and debt ceiling risk could all be catalysts. But it’s highly unlikely that the US dollar’s downfall comes from an external shock, a deliberate attempt from a country or group of countries to present an alternative to the dollar. There is no possible alternative, unless China makes a U-turn on economic and financial policy, liberalizing its capital account and switching from subsidizing exports to supporting consumption. The odds of this occurring anytime soon are low. We’ll revisit that possibility in the 2030s.

Capital markets update

What we’ll be watching in September

September 14: European Central Bank (ECB) policy decision

- As of early September, markets see around a one-in-four chance that the ECB raises rates at its September meeting.

- The eurozone economy is much weaker than the US economy. It is exposed to a Chinese slowdown and its inflation crisis is mainly supply-driven. As such, the ECB is at risk of overtightening policy.

September 20: Fed policy decision

- The US economy is booming, making it an odd time for the Fed to pause. But markets see very low odds that the Fed raises rates at its September meeting.

- Inflation in the US has been easing. But nominal growth is still well above trend, and surging oil prices will push inflation — both headline and core — higher over the coming months. While we do expect the Fed to stand pat in September, we’ll be looking for hawkish messaging from Fed Chair Powell at the press conference.

September 21-22: Bank of Japan (BoJ) policy decision

- The BoJ timidly normalized policy at its July meeting by tweaking its yield curve control program.

- With core inflation sticking above 2%, and inflation expectations continuing to inch up, the BoJ could try to guide policy tighter at its September meeting. But it has a habit of moving slowly, and when investors least expect it. With markets still digesting the recent policy tweak, the BoJ will likely wait for its next move.

Emerging theme: Early signs of a Canadian recession

GDP growth for the second quarter came in at -0.2%, below the average economist’s forecast of 1.2%. This is the first outright negative major datapoint for Canada this year. Weakness had begun to emerge in indicators throughout the economy in past weeks (hours worked, employment rate, retail sales, PMIs). Nothing dramatic, but a bit of softening across the spectrum. This negative GDP print confirms the trend.

Household consumption, residential investment (what else is new?) and exports contributed to the disappointing print. Spending on durables and housing should drop further in the third quarter, as the recent 50 basis points (bps) of Bank of Canada hikes start to bite.

Non-residential investment is the standout: businesses are building stuff. This mirrors, to a much lesser degree, the jaw-dropping trend of subsidies-driven manufacturing investment south of the border. Business investment is a key driver of business cycles. In this case, we don’t think its strength will prevent a slowdown of the Canadian economy, but it will foam the runway.

One of our main views for the coming quarters is a divergence in the path of the Canadian and US economies. The US should keep chugging along, while Canada’s economy grinds to a halt. In the US, monetary policy is less constraining, government spending is providing massive short-term support and consumer balance sheets are healthier.

The Canadian economy grinds to a halt in Q2

Source: Statistics Canada.

Multi-Asset Strategies Team

Tactical investment views

Source: Mackenzie Investments

Note: The views expressed in this piece apply to products that are actively managed by the Multi-Asset Strategies Team.

Positioning highlights

Neutral equity: Our overarching macro view is that of a “delayed landing” for the rest of 2023: resilient growth (no recession in the US), sticky inflation and higher-for-longer rates. Growth momentum in the US is strong, with employment, investment and industrial production all showing resiliency over the past few months. A “no landing” scenario is both good and bad for stocks: financial conditions will tighten, putting pressure on valuations, but (nominal) company fundamentals should remain solid. We have a slight preference for international stocks in the equity mix. US stocks are more expensive after the recent AI-driven rally, and international stocks should benefit from solid nominal economic growth.

Underweight bonds: We believe inflation in the US will be sticky, and will stay well-above target for the rest of 2023. We do like certain pockets of fixed income on a relative basis, such as short-term Canadian government bonds and German bunds. However, we remain underweight bonds in general.

Commodity-exporting EM currencies: Commodity-exporting EMs are well situated to outperform in this macro environment. Their budgetary and external balances have improved given high global nominal growth and high commodity prices. Their central banks started raising rates much earlier than the rest of the world. As a result, they have generally reached the end of their tightening cycle, reducing the risk of overtightening into a recession. But the level of rates remains high, offering positive carry over most other currencies. On the other hand, we have a negative view on the currencies of Asian EM countries. Their external positions have severely deteriorated, and their interest rates are relatively low.

Japan policy divergence: The BoJ widened the tolerance around its 10-year yield target by 25bps back in December, and by an additional 50bps in July 2023. With the yen severely undervalued and core inflation rising quickly, the BoJ could take more steps towards tightening in 2023, sending rates higher. We currently overweight the Japanese yen in our funds, and dislike Japanese long-term government bonds.

Capital market returns in August

Notes: Market data from Bloomberg as of August 31, 2023. Index returns are for the period: 2023-08-01 to 2023-08-31. In order, the indices are: MSCI World (lcl), BBG Barclays Multiverse, S&P 500 (USD), TSX Composite 60 (CAD), Nikkei 225 (JPY), FTSE 100 (GBP), EuroStoxx 50 (EUR), MSCI EM (lcl), Russell 2000 - Russell 1000, Russell 1000 Value - Russell 1000 Growth, USA 10-year Treasury Future, CAN 10-year Gov't Bond Future, GBR 10-year Gilt Future, DEU 10-year Bund Future, JPN 10-year JGB Future, BAML HY Master II, iBoxx US Liquid IG, Leveraged Loans BBG (USD), Provincial Bonds (FTSE/TMX Universe), BAML Canada Corp, BAML Canada IL, BBG Gold, BBG WTI, REIT (MSCI Local), Infrastructure (MSCI Local), BBG CADUSD, BBG GBPUSD, BBG EURUSD, BBG JPYUSD.