Highlights

- China’s economy has finally stabilized, a year and a half after the scrapping of its last COVID-19 restrictions.

- Government economic policies have rightsized the Chinese economy. But they can’t propel it back to pre-COVID growth rates, let alone drive its transition to developed economy status.

- China needs its own version of a New Deal, a massive stimulus to boost consumer spending. So far, the government has refused to explore such policies.

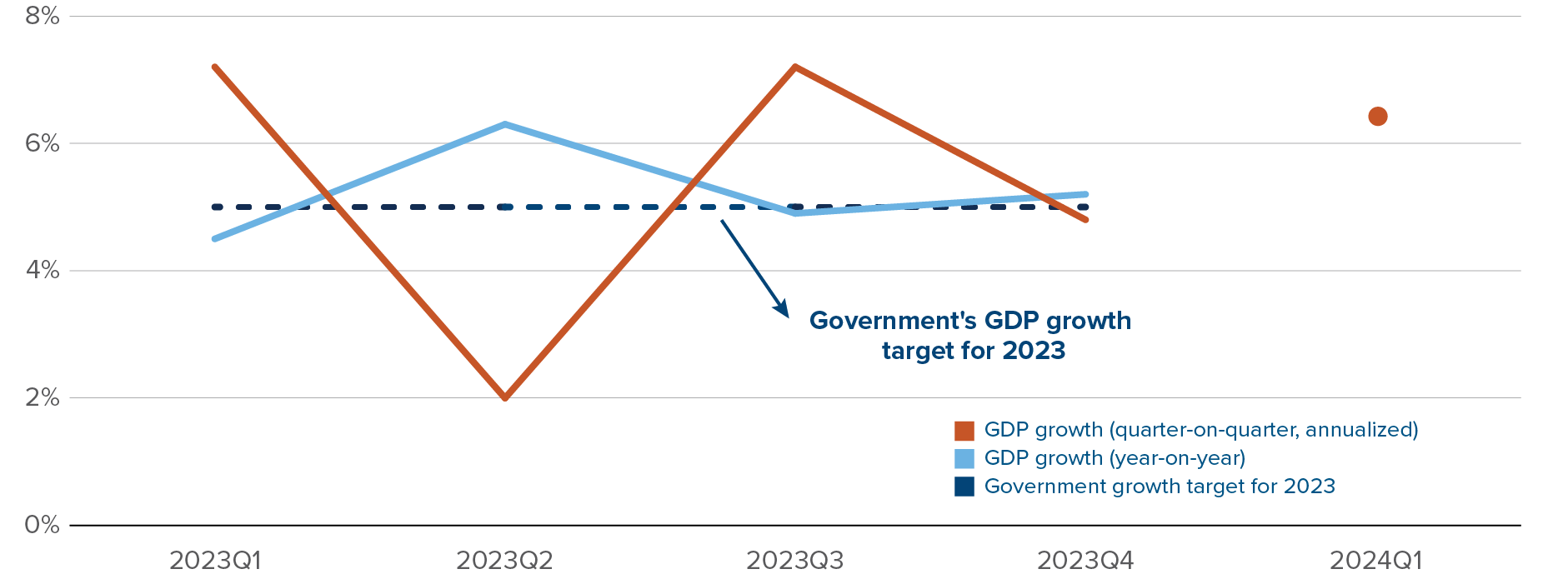

Unlike most Western economies, the Chinese economy didn’t come roaring back once unshackled from COVID restrictions. After the scrapping of its last COVID restrictions in November 2022, China did have a quick burst of “revenge spending” in the first few months of 2023. But with a real estate overhang and lacklustre government support, consumers retreated, and the bounce fizzled out in the second half of the year. To squeak by its 5% GDP growth target for 2023, China had to dump excess production onto world markets. A dose of creative accounting from Chinese officials was possibly also needed to reach the target.

China squeaked by its 2023 GDP target

GDP growth, China

Source: Bloomberg.

Source: Bloomberg.

The Chinese economy finally stabilized in the first half of 2024, thanks to rebounding global demand for goods exports and fresh efforts by the government to stop the deleveraging spiral in real estate. In 2022 and 2023, to contain the real estate crisis, the government relied on piecemeal help for developers, geared towards completing ongoing construction projects. But completing projects isn’t enough. The government must make sure that consumers can finance and purchase those completed homes. And it should bring excess buildings — which don’t fit consumer needs — onto its own balance sheet, demolishing when required, all while punishing bad actors among developers. Because local governments don’t have the fiscal space required for sweeping policies to balance out the housing market, the central government absolutely needs to step in.

The real estate measures announced in 2024 to date are more promising. A cut in required downpayment ratios will boost access to credit, and an ambitious program to turn unsold homes into public housing should help the housing market better digest new construction.

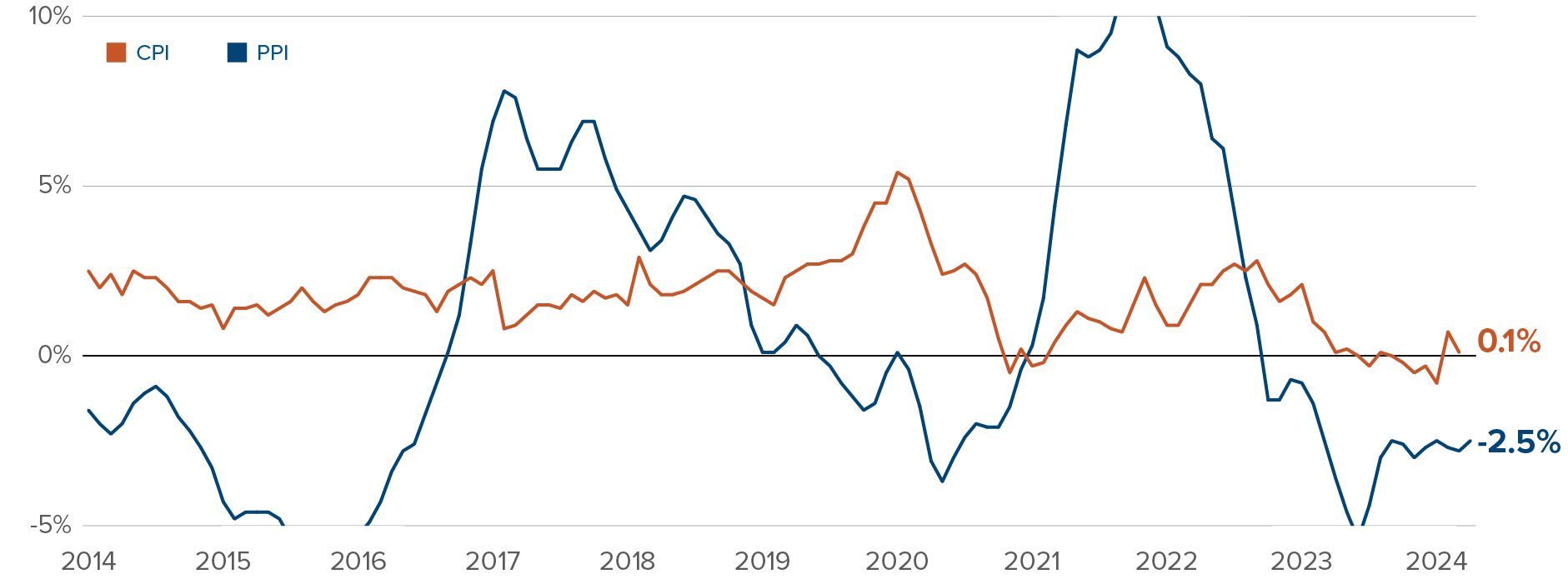

But even those measures are far too timid. A crude tally of measures to support the housing markets gets us to around ¥1 trillion ($200 billion CAD), compared to a cumulative shortfall in home sales of ¥6 trillion ($1.1 trillion CAD). Although it has stabilized, the Chinese economy is stuck in the mud, close to deflationary territory.

The spectre of deflation looms large

Year-on-year inflation, China

Source: Bloomberg.

Source: Bloomberg.

China needs its own version of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, a massive multi-year stimulus program to boost consumer spending, clean up bad debt from the real estate fiasco and transform China into a modern consumer-driven economy. Bad debt is hidden in local government and state-owned enterprise balance sheets, forcing them to counterproductively tighten the purse strings. Meanwhile, the central government’s balance sheet is squeaky clean. Central government debt in China is around 25% of GDP, much lower than that of every G20 country. Global demand for Chinese government bonds is solid, and its humongous trade surplus would contribute to easy financing of stimulus spending.

In the 1930s United States, total spending for New Deal policies reached 40% of GDP over half a decade. A similar scale program in China could:

- - Clean up the real estate market. Take control of failing developers — after wiping out equity holders. Ease credit to facilitate homebuying. Demolish when needed.

- - Take the heat off local governments. Much of the debt in the Chinese economy is owed by local governments. Because land sales — local governments’ primary source of revenues — have ground to a halt, municipalities have stopped borrowing, instead focusing on paying down existing loans. That is a huge drag on domestic Chinese growth. The central government could extinguish that “hidden” debt by exchanging it for national bonds.

- - Build a social safety net. Chinese workers need to store away a large proportion of their earnings to face unanticipated shocks, including job losses. Reducing the need for precautionary savings through welfare programs would unlock consumer spending.

However, the Chinese government has been averse to such large-scale spending programs. Perhaps because of a general aversion to Western-style welfare. Perhaps because it would be rebalancing the economy away from exporting firms — the pride of the Chinese development story — towards consumers. Perhaps because it would increase reliance on foreign countries, both when financing the stimulus through bond issuance and when importing the goods and services purchased by newly emboldened Chinese consumers.

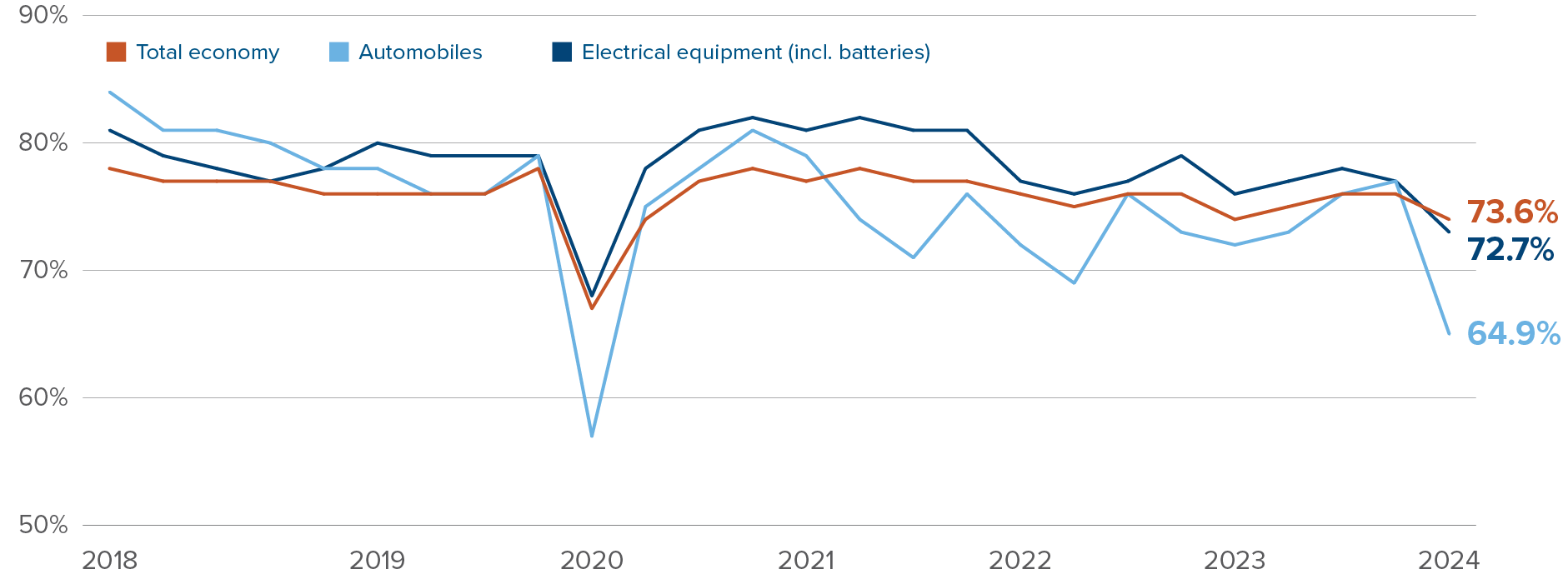

Instead of relying on consumers, the government keeps betting on exports to reach its GDP growth target. That strategy — providing cheap financing to favoured exporting industries — was a resounding success in the 1990s and 2000s, but it can’t work today. China’s trade surplus — the difference between its exports and imports — is already historically large. Combine that with the sheer size of the Chinese economy, and, at around 2%, its manufacturing trade surplus as a proportion of the world economy is approaching never-before-seen territory.

Someone needs to absorb those ballooning Chinese exports, and that won’t happen without a fight. Around the world, there is mounting resistance to Chinese dumping of exports and slumping manufacturing imports. The resulting decimation of domestic factories is an economic and political headache for the US and Europe. It is also a national security risk: importing critical manufactured goods is a feasible model in peacetime, but not in wartime. Europe is most at risk from China’s economic model. Chinese-made vehicles already make up one-quarter of all-electric vehicle sales in Europe. With China unable to sell its car factory production into its weakening domestic car market, its push to export will only accelerate. And Europe is particularly defensive of its storied car industry.

Chinese factories are running below capacity

Capacity utilization, China

Source: Bloomberg.

Source: Bloomberg.

If the Chinese government doesn’t pivot to boosting consumption, its current economic policies will almost inevitably trigger a global trade war. The Biden administration recently introduced tariffs on a few strategic goods. Those won’t break China’s resolve, nor have a material impact on the Chinese economy. The new US tariffs only cover 2% of Chinese exports to the US and 0.5% of total Chinese exports. But with European governments likely to soon join the protectionist party — they didn’t when Trump imposed tariffs on China back in 2018 — there’s a risk of an escalation.

Neither tariffs, political pressure, nor economic logic will convince the Chinese government to pivot from subsidizing exports to supporting consumer spending and balancing out the housing market. Low interest rates, which in China effectively transfer wealth from consumers (generally savers) to businesses (generally borrowers) will persist.

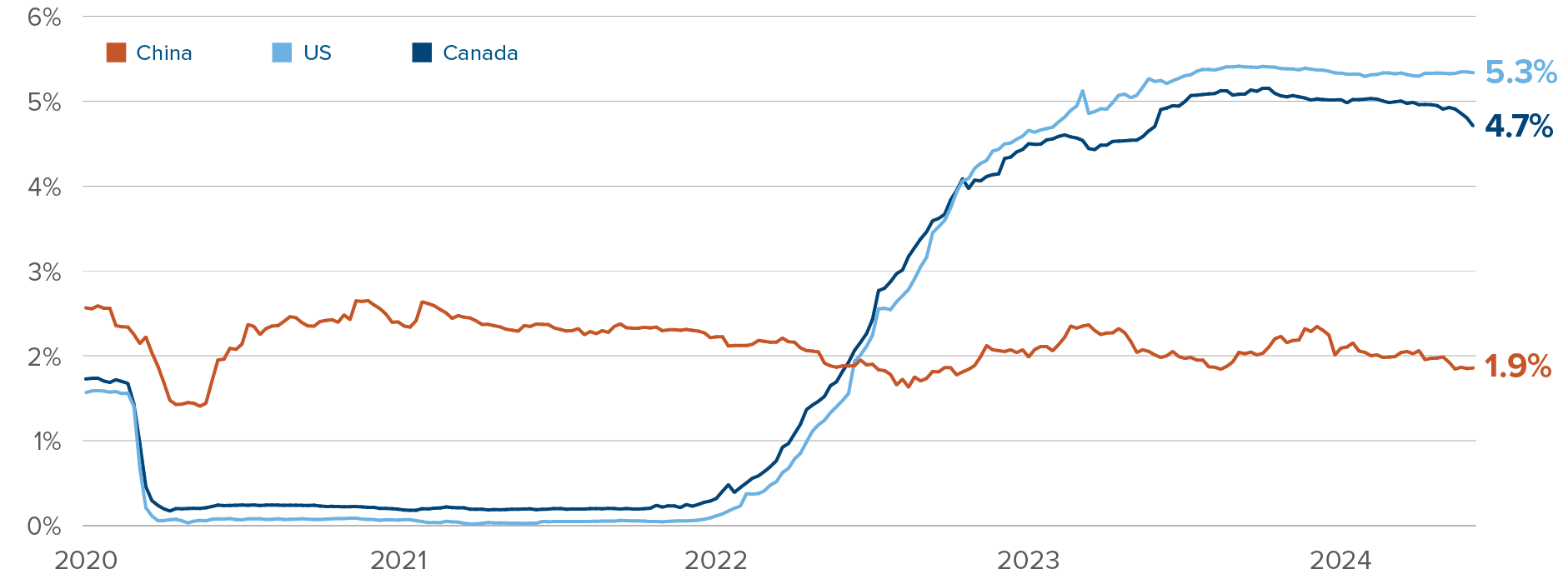

The China-US interest rate spread is at an all-time high

Three-month cash rates

Source: Bloomberg.

Source: Bloomberg.

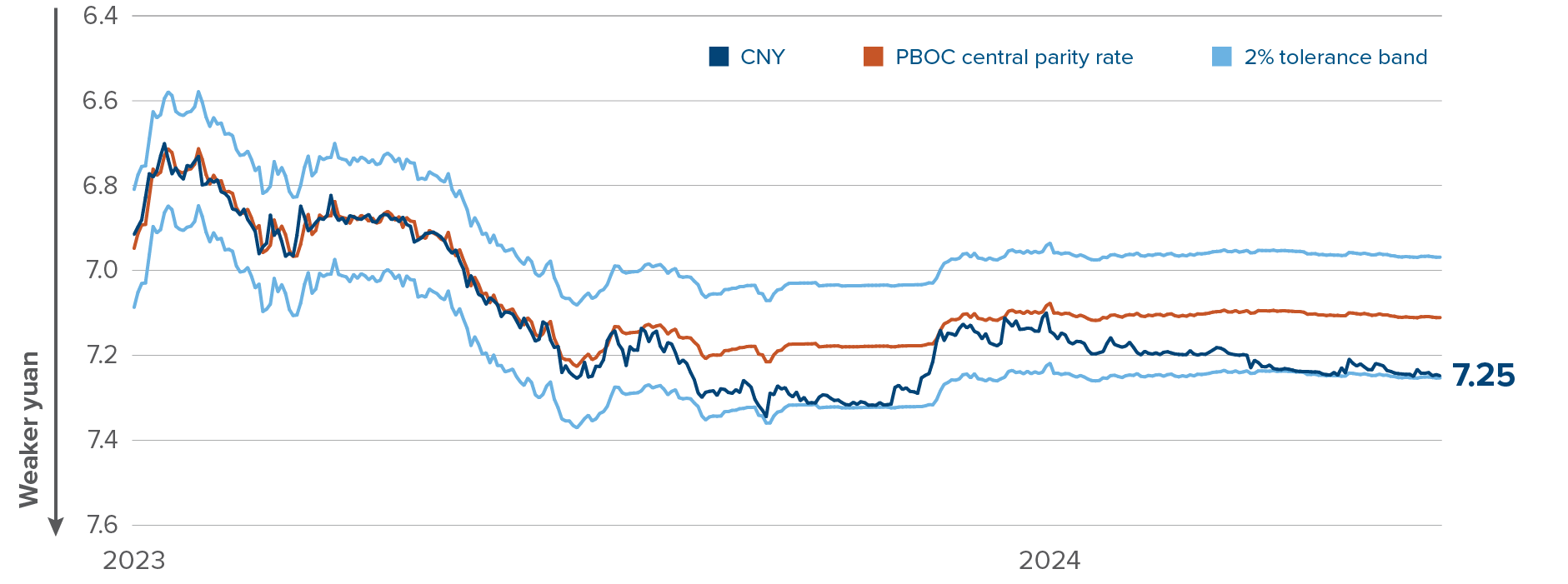

The gaping rate differential between China and the US should continue to put pressure on the Chinese yuan. While Chinese authorities won’t want a volatile drop in the yuan’s value, they are probably satisfied with general yuan weakness. They recently stopped forcing the yuan to stay anchored at the “fix”— the People’s Bank of China guidance for the exchange rate.

Chinese authorities have allowed the yuan to drift lower

CNY per USD

Source: Bloomberg, Council on Foreign Relations.

Source: Bloomberg, Council on Foreign Relations.

A continually weak yuan will be critical to China’s strategy of using exports as an escape valve for factory overcapacity. In many industries, China is technologically dominant and cost-effective. Hence, ramping up manufacturing exports to solve factory overcapacity won’t be too much of an economic issue. But a cheap currency also helps. Accordingly, we are short the Chinese yuan in the Mackenzie Global Macro Fund. We think China should rebalance away from exports and implement its own version of a “New Deal”. But ultimately, we think it is unlikely to do so.

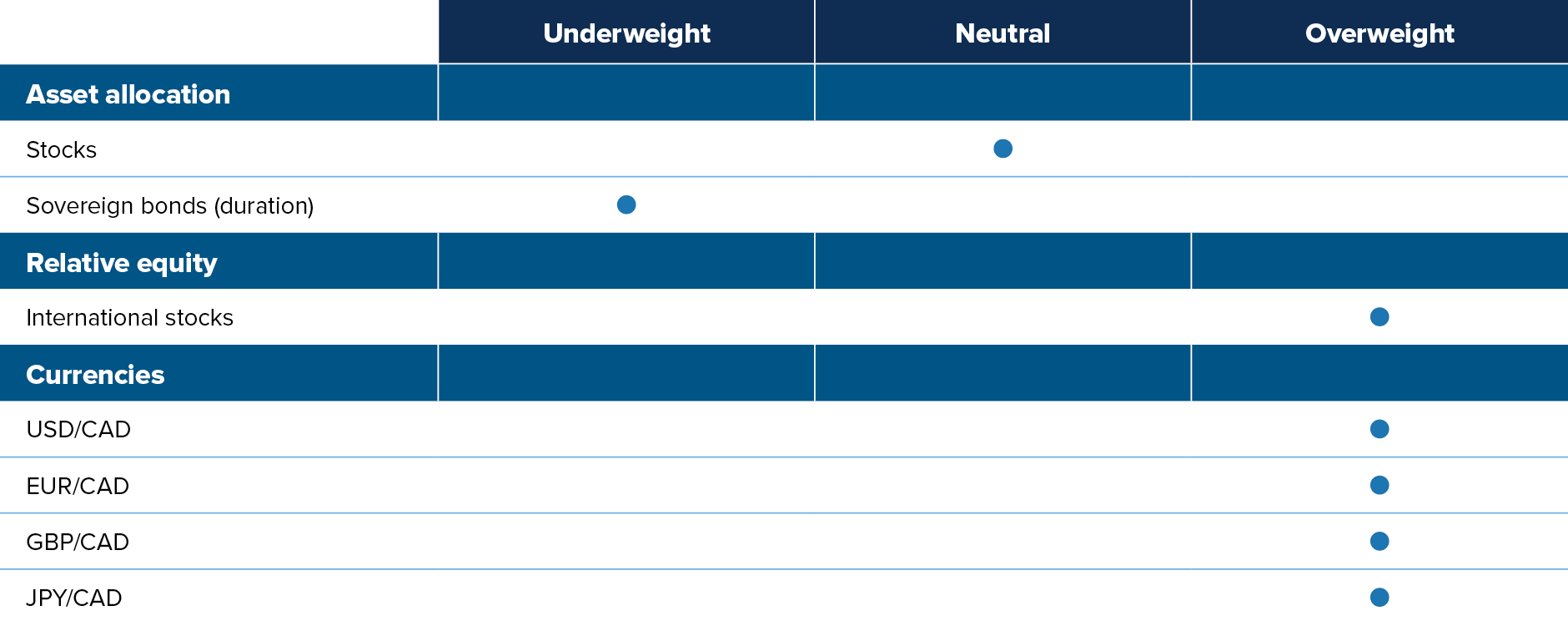

Multi-Asset Strategies Team’s investment views

Tactical summary

Note: The views expressed in this piece apply to products that are actively managed by the Multi-Asset Strategies Team.

Positioning highlights

Overvalued US assets: We generally don’t like US assets, whether equities, bonds or the US dollar. International stocks had a solid end to 2023, as expectations of US Federal Reserve interest rate cuts caused the US dollar to lose ground and international stocks to rally. That momentum has extended into 2024. Not only do international stocks generally have more attractive valuations than North American assets, but they should also benefit from promising macro catalysts ahead. The Spanish, Italian and Japanese stock markets screen particularly well across the board. Within US equity markets, we prefer small-cap stocks: valuations are more attractive than large caps and market sentiment is improving.

Moving to rate-sensitive sectors: Health care stocks look less attractive going forward. Health care was one of the best-performing sectors in May and the top positive contributor to our sector strategy. But we closed that position towards the end of the month, with signs of deteriorating fundamentals starting to worry us. Analyst forecasts have turned down sharply. Plus, macro signals are favourable to more rate-sensitive sectors like real estate, which is now one of our favourite sectors.

Canadian landing: The macro situation in Canada is much more dire than in the US. The Canadian economy is arguably the worst-performing economy in the first half of 2024. The job market is deteriorating quickly, especially when adjusting for working population growth and government hiring. We have been adding to our short Canadian dollar position, already one of the largest bets in the Mackenzie Global Macro fund.

Commodity-exporting EM currencies: Commodity-exporting EMs are well situated to outperform in this macro environment. Their budgetary and external balances have improved amid high global nominal growth and high commodity prices. Their central banks started raising rates much earlier than the rest of the world. As a result, they have generally reached the end of their tightening cycle, reducing the risk of overtightening into a recession. But the level of rates remains high, offering positive carry over most other currencies. On the other hand, we hold a negative view of the currencies of Asian EM countries. Their external positions have severely deteriorated and their interest rates are relatively low.

Mexican peso’s run is probably over: We flipped from a long position to a short position at the start of May. After a great run over the past few years, the Mexican peso now screens as one of the most overvalued currencies globally. It still benefits from double-digit interest rates in Mexico, but investor sentiment has been weakening quickly. Plus, political risks won’t do anything to change the trend of deteriorating positioning and sentiment.

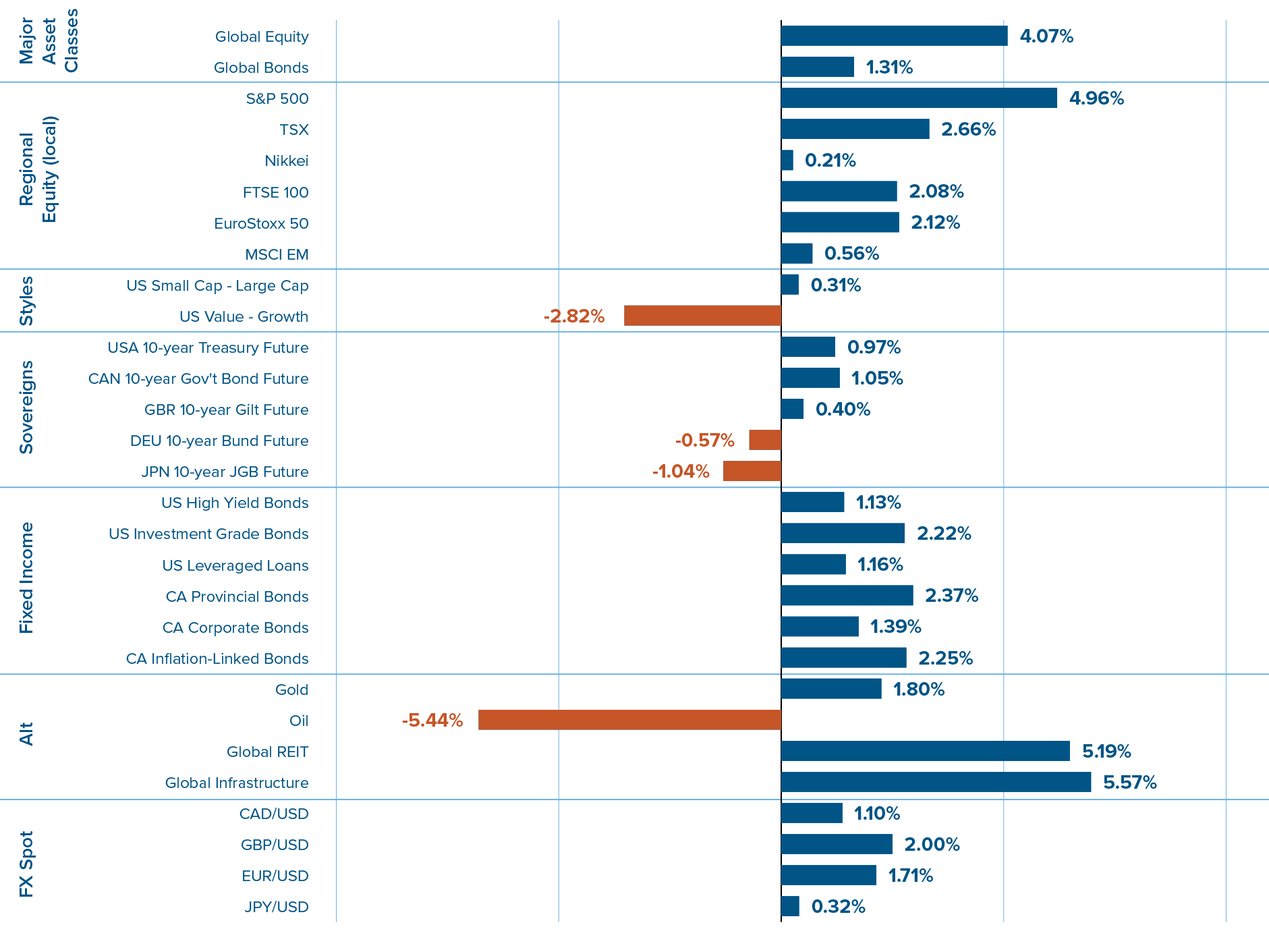

Capital market returns in May